The Colonial Era: Fasting for Survival

An ominous fleet of French ships were sited off the coast of Massachusetts, striking fear into the American Colonists. The French Admiral, D’Anville, commanded the most powerful fleet at the time, including 70 ships and 13,000 troops. The Admiral planned to recapture Nova Scotia and attack the Colonies successively from Boston to Georgia.

Massachusetts Governor, William Shirley, proclaimed a fast, imploring the Colonists to pray to God for deliverance from peril. Reverend Thomas Prince prayed with his congregants at the Old South Meeting House:

“Deliver us from our enemy! Send Thy tempest, Lord, upon the waters to the eastward. Raise Thy right hand. Scatter the ships of our tormentors and drive them hence. Sink their proud frigates beneath the power of Thy winds!”

Parishioners testified that the sunny, calm day immediately darkened; a violent wind was heard against the windows followed by the church bell ringing wildly. Reverend Prince finished his prayer with weeping:

“We hear Thy voice, O Lord! We hear it! Thy breath is upon the waters to the eastward, even upon the deep. Thy bell tolls for the death of our enemies!! Thine be the glory, Lord. Amen and Amen!”

In an act of desperation, D’Anville poisoned himself upon witnessing two thousand of his soldiers die, and another four thousand fall ill due to the violent tempest on the sea. The French fleet was nearly destroyed, prompting the Colonists to liken it to Pharaoh’s army perishing in the Red Sea, and the destruction of the Spanish Armada.

Governor Shirley testified before the Massachusetts Legislature stating that such a direct act of providence never was witnessed before. Therefore, a Day of Prayer and Thanksgiving was proclaimed to thank God for His deliverance.1

This conspicuous act of Providence in American History is so extraordinary that even atheists would be hard pressed to deny that God intervened. From America’s inception, corporate Days of Humility, Prayer and Fasting were practiced together, along with specific prayers for circumstances facing the nation. Prayer and Thanksgiving days often followed the fast days, proclaiming corporate thankfulness for their answered prayers.2

“Humiliation” or “afflicting one’s soul” began with the Day of Atonement, found in Leviticus 16:29-30; 23:27-29; and Numbers 29:7. Also known as Yom Kippur, The Day of Atonement is the holiest day of the year in the Jewish calendar. The Hebrew word for afflict is עָנָה, which is transliterated as ʻânâh. The etymology of ʻânâh is to humble oneself and be brought down low, rendering humility as the foundation of fasting.

Therefore, affliction is a humbling of oneself before God to reflect upon one’s sins for repentance. Repentance prepares the heart to connect with God in prayer, while simultaneously fasting for spiritual effectiveness. Without humility, prayer and fasting lack the full spiritual power available to believers.

“Also the tenth day of this seventh month shall be the Day of Atonement. It shall be a holy convocation for you; you shall afflict your souls, and offer an offering made by fire to the Lord. And you shall do no work on that same day, for it is the Day of Atonement, to make atonement for you before the Lord your God. For any person who is not afflicted in soul on that same day shall be cut off from his people.” (Lev. 23:27-29)

In 1619, Pastor John Robinson preached a sermon from Ezra 8:21 before the Pilgrims left Leyden, Holland aboard the Mayflower.3 Ezra is an account of the Jews, who were exiled to Babylon at that time. The passage details their migration back to their Promised Land under Cyrus the Great. Due to the circumstances of the Pilgrims in Leyden, it was perfectly fitting for the pastor to preach from this passage and hold a corporate fast before embarking on their long and dangerous journey.

“There, by the Ahava Canal, I proclaimed a fast, so that we might humble ourselves before our God and ask him for a safe journey for us and our children, with all our possessions.” (Ezra 8:21)4

The Pilgrims set sail for Jamestown, but due to “crosse winds” and “many feirce storms,” they landed in 1620 at what eventually became the Massachusetts Bay Colony.5 Acknowledging God’s providence, they had only God’s Spirit and His grace to sustain them.6 Humiliation, prayer, and fasting became a way of life for their very survival.7

Starvation, harsh weather, and the threat of Native attacks not only permanently fixed corporate Days of Humility, Prayer and Fasting into the American way of life, it most likely saved the nation. Thus, the first Thanksgiving became a week long celebration of God’s provision for sustaining their lives in an uncharted wilderness.8

The majority of prayer and fast days kept by the Colonists have been lost to history. Of the New England documents which survived, 1,052 fast days and 697 thanksgiving days were recorded between the years 1620 and 1815. The majority of these fasts, 1,448 of them, were public (corporate) fasts enacted by the magistrates, while 270 fasts were enacted by individual churches.9

The Colonists’ belief in Divine Providence induced them to pray for any perceived threat. The majority of the fasts centered on their food supply including hunger, drought, severe weather, and insects threatening their crops.10 They also fasted due to sickness or epidemics, which they called plagues.11

They fasted before a church was established, and before a minister was ordained and/or installed in a church.12 They fasted due to Native attacks and abductions, and for peace with the Natives.13 They also fasted for their local governments, their liberties, and for the enactment of their laws.14 The most striking aspect is the faith of the Colonists, not only to fast, but in their expectation that God would move on their behalf.

The Revolutionary Era: Fasting For Freedom

An examination of nearly 7,400 Colonial newspapers revealed that from the year 1690 and beyond, Colonial governments regularly proclaimed days of “solemn FAST, PRAYER and HUMILIATION before Almighty God” in the Colonial newspapers. The newspapers subsequently printed the supernatural results of the fasts by detailing God’s Divine intervention among the people. The newspapers were utilized for the collective power of the people to implore God to intercede on their behalf, and for collective thanksgiving to God for His provision.15

The Colonists shaped American History with their appointed Days of Humility, Prayer and Fasting, setting a precedent and a heritage which continued through the Revolutionary Era and into the 20th Century. A publicly appointed corporate Day of Prayer and Thanksgiving Day are still observed in 21st Century America.

Presidents, governors and churches continued to appoint fast and thanksgiving days during the War for Independence, and well after the Constitution was ratified. From 1774 to 1783, all appointed days for prayer and fasting enumerated specific concerns during the war, but they broke tradition in one aspect—they exchanged the legendary “God Save the King” for “God Save the People.”16

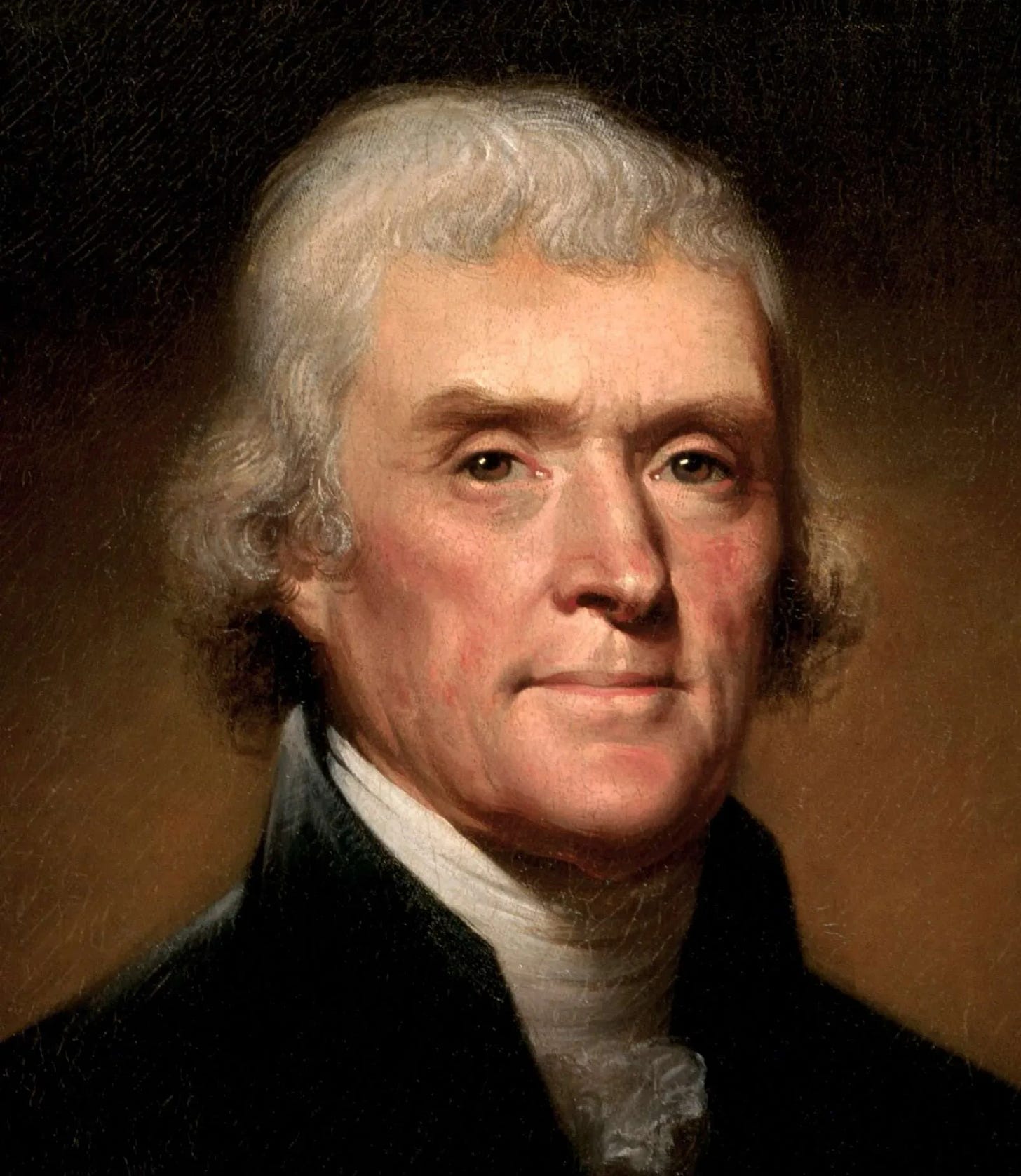

As relations with England deteriorated, Thomas Jefferson, the governor of Virginia at that time, proclaimed a fast due to the blockade of Boston, stating,

“. . . the said first Day of June be set apart by the Members of this House as a Day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer, devoutly to implore the divine Interposition for averting the heavy Calamity, which threatens Destruction to our civil Rights, and the Evils of civil War. . .”

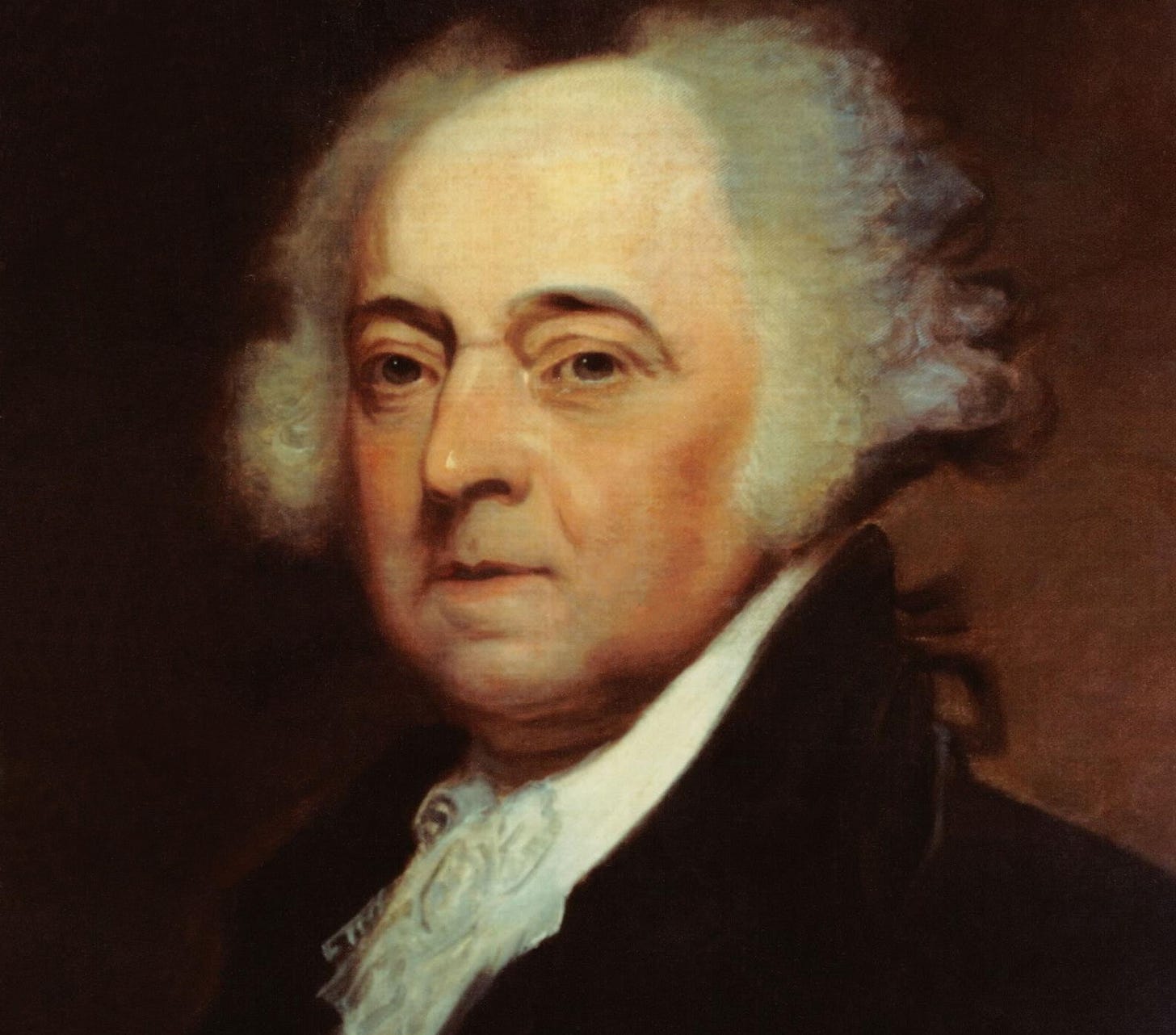

The Continental Congress proclaimed many fasts during the Revolution; one of which prompted John Adams to write to his wife Abigail, celebrating that:

“Millions will be upon their Knees at once before their great Creator, imploring his Forgiveness and Blessing, his Smiles on American Councils and Arms.”

George Washington issued many fast days during his military and political career, including during his plight at Valley Forge. Washington also issued a prayer and thanksgiving day after the passage of the Bill of Rights.

“The Honorable Congress having thought proper to recommend to The United-States of America to set apart Wednesday the 22nd instant to be observed as a day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer, that at one time and with one voice the righteous dispensations of Providence may be acknowledged & His Goodness and Mercy towards us and our Arms supplicated and implored—The General directs that this day also shall be religiously observed in the Army, that no work be done thereon & that the Chaplains prepare discourses suitable to the Occasion. . .”

During his presidency, John Adams declared a fast day for God’s protection due to impending war with France in March of 1798. Adams proclaimed, “a day of Solemn Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer,” in which no work was to be done, instead, repentance led by the Holy Spirit. Adams proclaimed a similar fast one year later quoting Proverbs 14:34—that only righteousness exalts a nation.

During the War of 1812, President James Madison appointed days for prayer and fasting three separate times. In his 1813 call for prayer and repentance, Madison acknowledged America as a Christian nation. In his 1814 proclamation, Madison proclaimed “a day of Public Humiliation and Fasting, and of Prayer to Almighty God” for the safety and welfare of the United States, blessings on their arms, and a return to peace. Madison notes humility to the sovereignty encouraging the people in “. . . humble adoration to the Great Sovereign of the Universe, of confessing their sins and transgressions. . .”

In 1849, President Zachary Taylor issued “a day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer” due to a cholera epidemic, stating, “At a season when the providence of God has manifested itself in the visitation of a fearful pestilence, which is spreading itself throughout the land, it is fitting that a people, whose reliance has ever been in his protection, should humble themselves before his throne; and, while acknowledging past transgressions, ask a continuance of the Divine mercy.”

President Abraham Lincoln issued two fast days during the civil war, one of which Lincoln quotes directly from Madison’s 1813 proclamation, admonishing the people to observe an, “offering of fervent supplications to ‘Almighty God for the safety and welfare of these States, His blessings on their arms, and a speedy restoration of peace . . .’"

Lincoln’s desperation is evident in his second appointed civil war fast. In keeping with America’s heritage, he used the phrase, “a day of national humiliation, fasting, and prayer,” but adds “national” to the triad. His proclamation is similar to those of the Colonists and Founders, requesting that no work be done on that day. His moving words still evoke patriotism mixed with a desire for repentance:

“. . .May we not justly fear that the awful calamity of civil war which now desolates the land may be but a punishment inflicted upon us for our presumptuous sins, to the needful end of our national reformation as a whole people? We have been the recipients of the choicest bounties of Heaven; we have been preserved these many years in peace and prosperity; we have grown in numbers, wealth, and power as no other nation has ever grown. But we have forgotten God. We have forgotten the gracious hand which preserved us in peace and multiplied and enriched and strengthened us, and we have vainly imagined, in the deceitfulness of our hearts, that all these blessings were produced by some superior wisdom and virtue of our own. Intoxicated with unbroken success, we have become too self-sufficient to feel the necessity of redeeming and preserving grace, too proud to pray to the God that made us.

It behooves us, then, to humble ourselves before the offended Power, to confess our national sins, and to pray for clemency and forgiveness.

Now, therefore, in compliance with the request, and fully concurring in the views of the Senate, I do by this my proclamation designate and set apart Thursday, the 30th day of April, 1863, as a day of national humiliation, fasting, and prayer.”

President Woodrow Wilson is the last president to use the triad, Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer when he proclaimed a fast day in 1918 due to World War I. During World War II, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt read a prayer on D-Day, but fell short of proclaiming a Day of Prayer, and did not implore Americans for humility nor fasting.

His successor, President Harry S. Truman, appointed a Day of Prayer after the Japanese surrendered, but also failed to include humility and fasting in his proclamation. Subsequently, Truman instituted a National Day of Prayer as an annual observance.

President Ronald Reagan proclaimed the first Thursday of May as the annual observance for the Day of Prayer, but neglected to include fasting and humility.

President George Bush issued a National Day of Prayer and Remembrance after the worst terrorist attack on American soil, and after Hurricane Katrina, but failed to beseech Americans to pray, nor acknowledge fasting or humility.

President Donald Trump issued a National Prayer Day in 2020. To his credit he acknowledged Divine Providence and quoted Washington’s proclamation from the Revolution: “General George Washington proclaimed a national day of ‘fasting, humiliation and prayer, humbly to supplicate the mercy of Almighty God.’"

He encouraged Americans to pray, but offered no admonition for humility or fasting, and neglected to appoint a specific Day of Prayer for the pandemic.

The Modern Era: Fasting to Shape History

During the 1790’s, American believers, including Baptists, Presbyterians and Methodists, fasted and prayed for revivals, especially after the decline of the First Great Awakening.17 This practice transcended denominational barriers and God poured out a Second Great Awakening.

There are two types of fasts in the Bible, personal and corporate. Although the Colonists employed both, it was their corporate fasts which shaped American History since the beginning. This spiritual tool has been sought after throughout much of America’s history, but due to modern Biblical and historical ignorance, it has been lost to modern believers.

Corporate prayer and fasting is a powerful spiritual tool which God gifted believers to shape their personal and national history. With the advent of social media, believers now have a media tool to enact corporate “Days of Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer,” reaching far more people than ever before in American History.

It is long overdue for American believers to enact this spiritual tool once again and experience God’s providential mercies move across our nation, heal our land, pour out revival, and save the Nation.

Catherine Drinker Bowen, John Adams and the American Revolution, (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1951), 10-12.

William DeLoss Love, Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England, (New York: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1895), p12. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=iau.31858015843042&seq=9&q1=fasting.

Alexander Young, Chronicles of the Pilgrim fathers of the colony of Plymouth, From 1602 to 1625, (Boston: C.C. Little and J. Brown, 1841), 380-382.

Ibid., 87.

William Bradford and Charles Deane, History of Plymouth Plantation, (Boston: Privately Printed, 1856), 75.

Ibid., 79.

William DeLoss Love, Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England, 70.

Ibid., 76.

Ibid., 514.

Ibid., 102; 178; 318; 180.

Ibid., 142.

Ibid., 110.

Ibid., 132-35.

Ibid., 148; 158; 87.

David A. Copeland, “In All the Papers: Reporting on Religion in Colonial America,” American Journalism vol. 13, 4 (1996): 396-400.

William DeLoss Love, Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England, 336; 340.

Thomas S. Kidd and and Barry G. Hankins, Baptists in America: A History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2015), 84.

This article is exceptionally well-researched and thoughtfully presented. The attention to detail, particularly in connecting historical events with scriptural principles, is truly impressive. The integration of historical narratives with theological insights provides a deeper understanding of how fasting and prayer have shaped pivotal moments in American history. Thank you for highlighting such a meaningful aspect of our heritage with such clarity and depth.

Very good!